How do we make sense

of the persistent pattern of unjust violence against Black Americans? How can we begin to situate police misconduct within America’s historical context? And how can we critically evaluate and creatively reimagine schools, police, courts, and prisons to ensure that every American can live a truly free life? Co-authored by Megan Wicks and Isometric Studio, this primer provides tangible steps to reimagine unjust systems from the ground up, examining and illustrating meaningful alternatives. This web page contains a preview of the 46-page PDF primer, which is available for free download at the link below.

Preview Slides from Primer

When we began writing this primer,

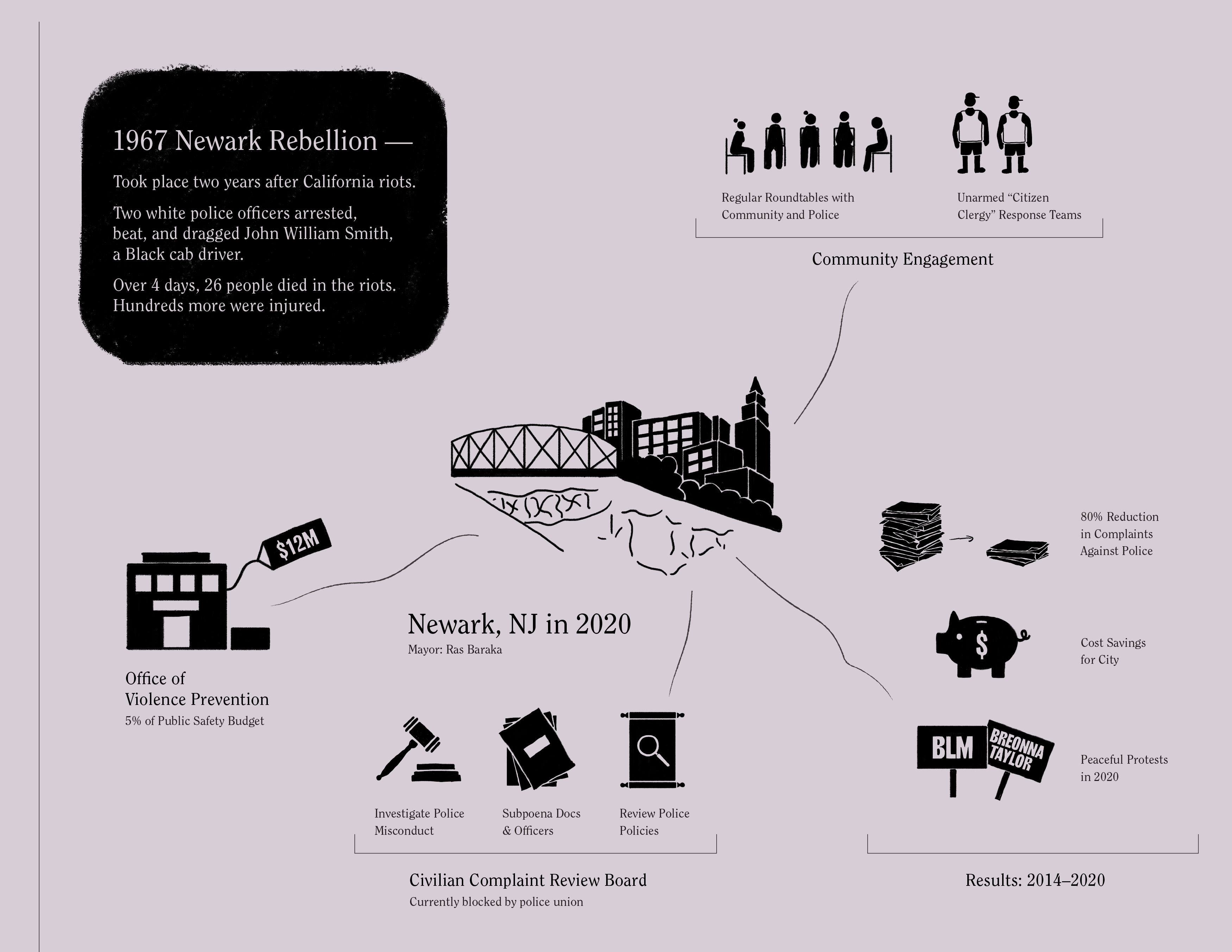

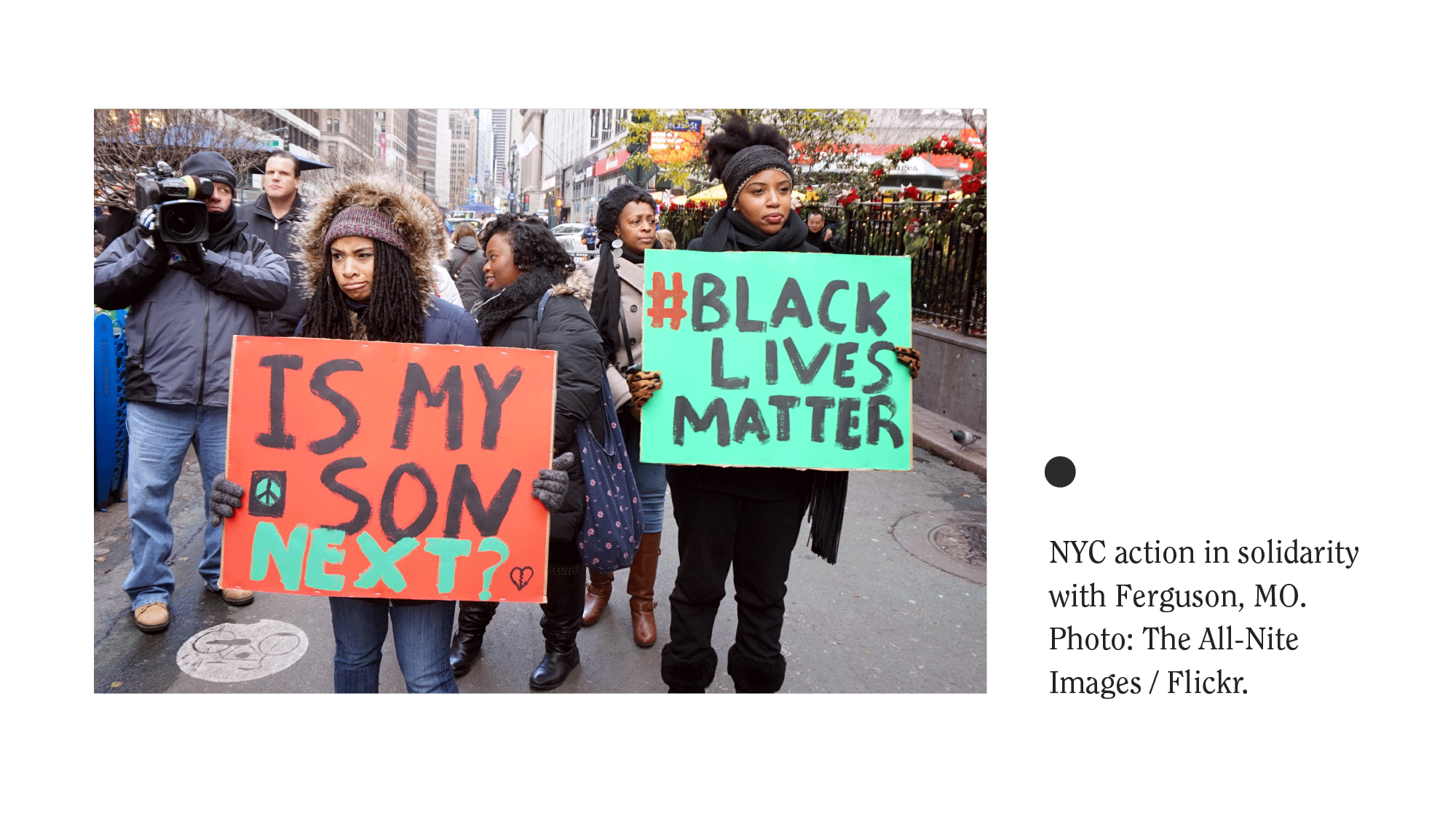

the city of Minneapolis had agreed to activists’ demands to “defund” and “dismantle” the police in the wake of the George Floyd murder. It has since walked back these promises, acceding to fears that abolishing the police would result in anarchy and violence—anxieties stoked by the Trump administration to demonize the Black Lives Matter movement. However, even prominent Black leaders like Newark Mayor Ras Baraka have labeled the “defund” movement as a “bourgeois liberal” idea that risks harming Black communities. This primer argues that we need to go beyond catchwords like “defund,” and to name and define the specific resources we offer as replacements. While we don’t have all of the answers, we aim to show how scholars and activists have tackled these issues by placing them within the context of history and lived experiences.

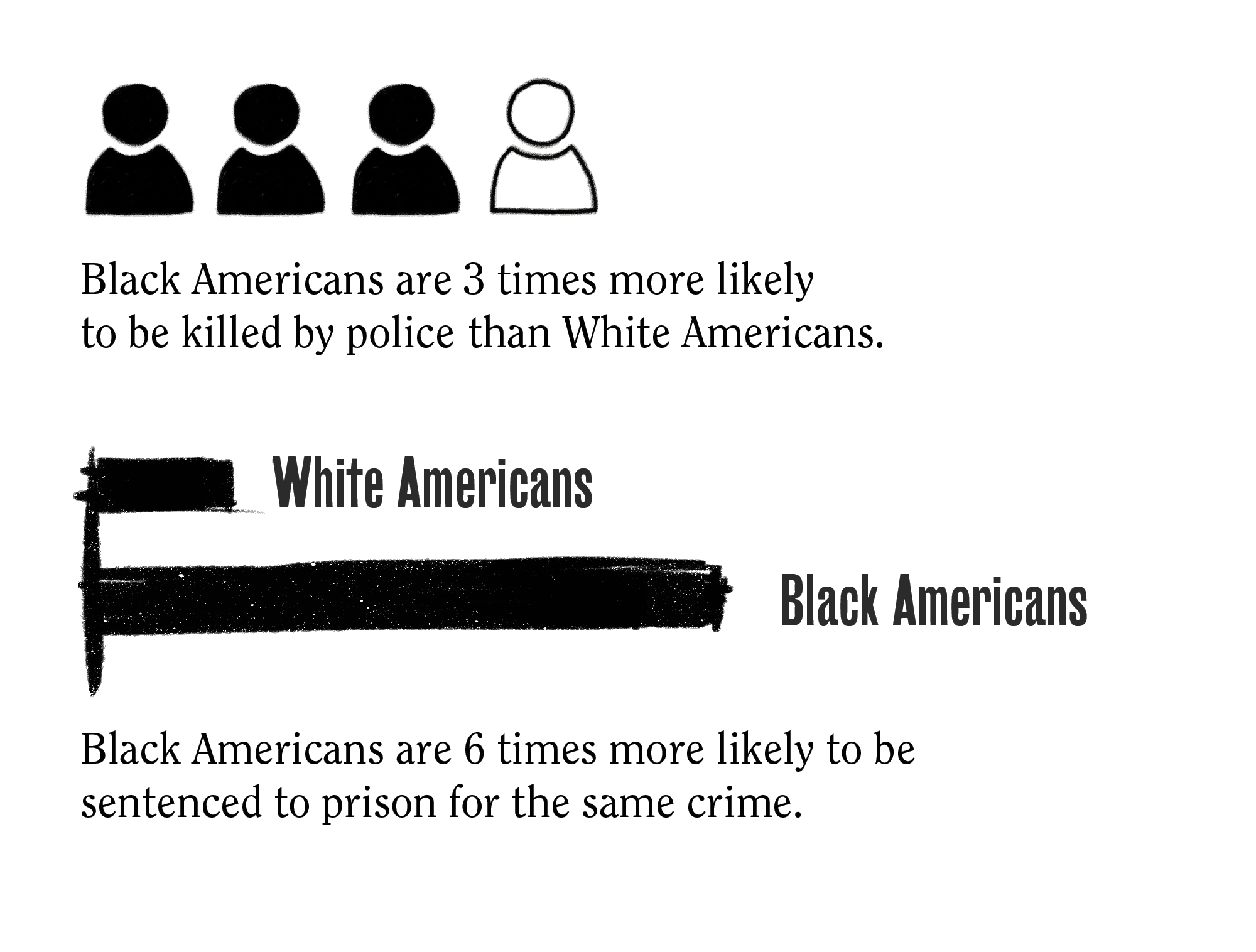

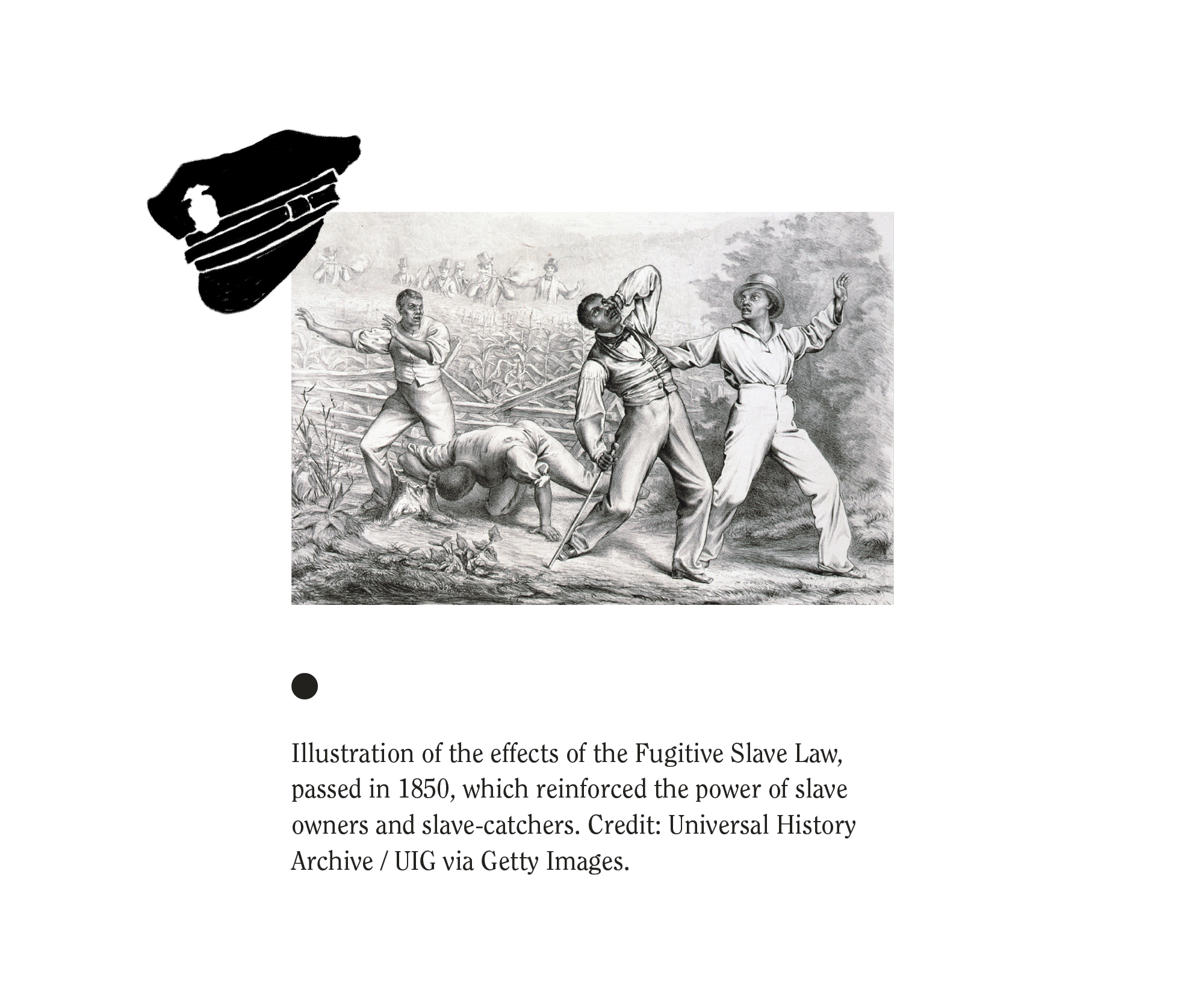

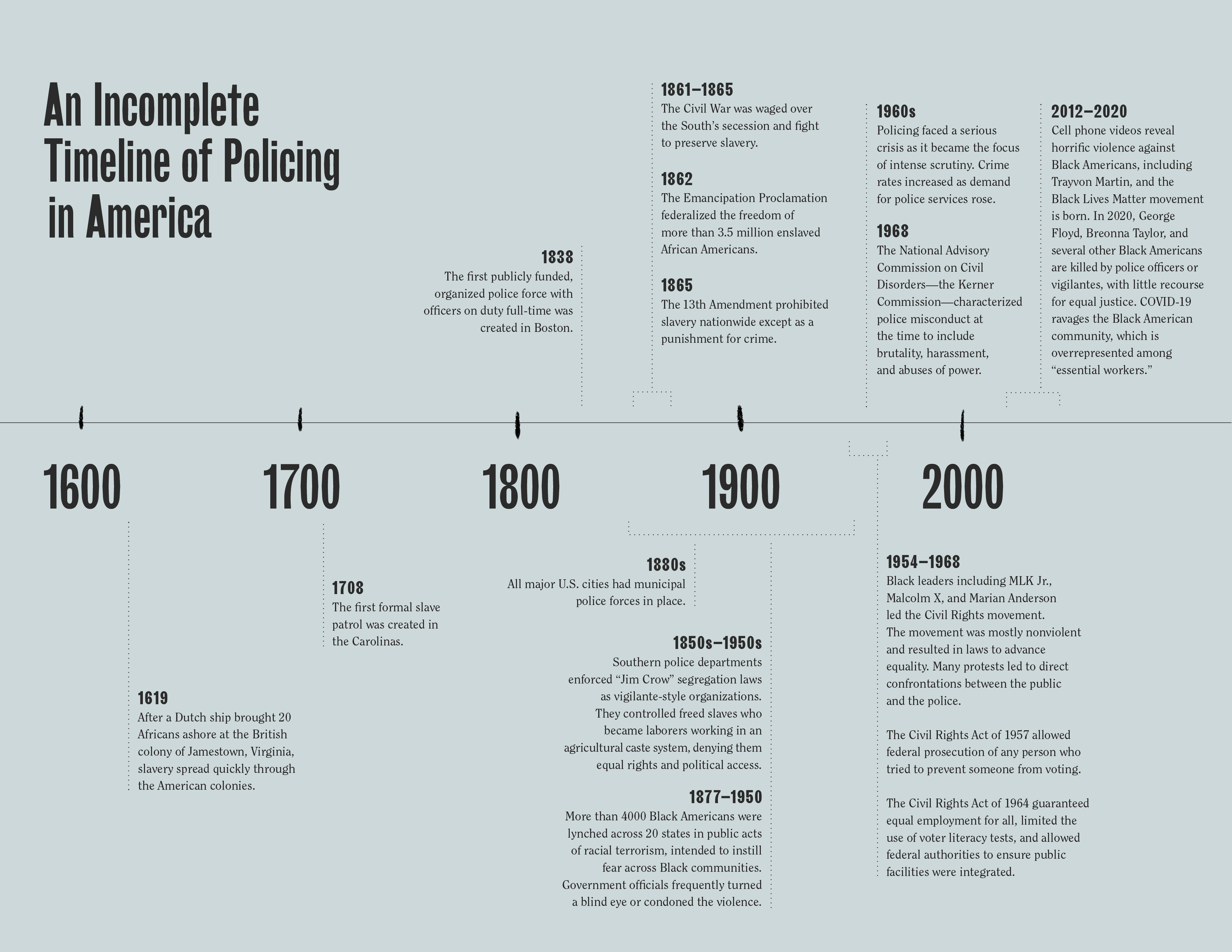

Modern American policing

has roots that can be traced back to slavery and business interests. In the South, slave patrols morphed into police after the abolition of slavery, and the prison-industrial complex was born as freed Black people were arrested en masse for petty and often fabricated crimes. While policing in the North wasn’t tied to slavery, it was nonetheless economically motivated and designed to protect the interests of the business elite at the expense of the working class, the poor, Black and brown people, and immigrants—overlapping social categories that existed at the bottom of the economic ladder and thus were the most vulnerable. This system continues to this day. The United States has the largest prison population in the world, with the highest number of Black people relative to their proportion of the general population. An analysis of policing and other institutions reveals parallels between the contemporary prison system and slavery of the past.

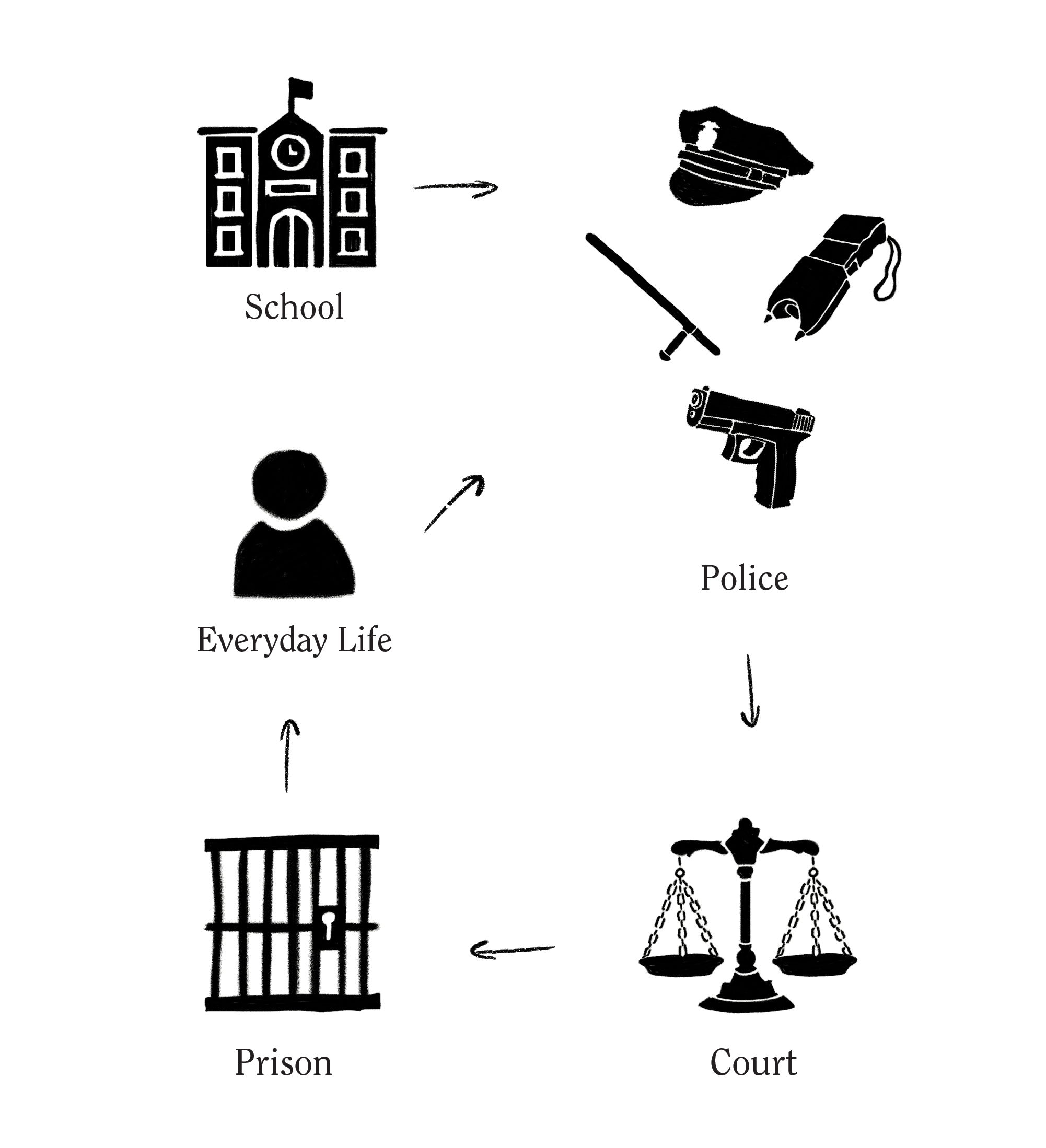

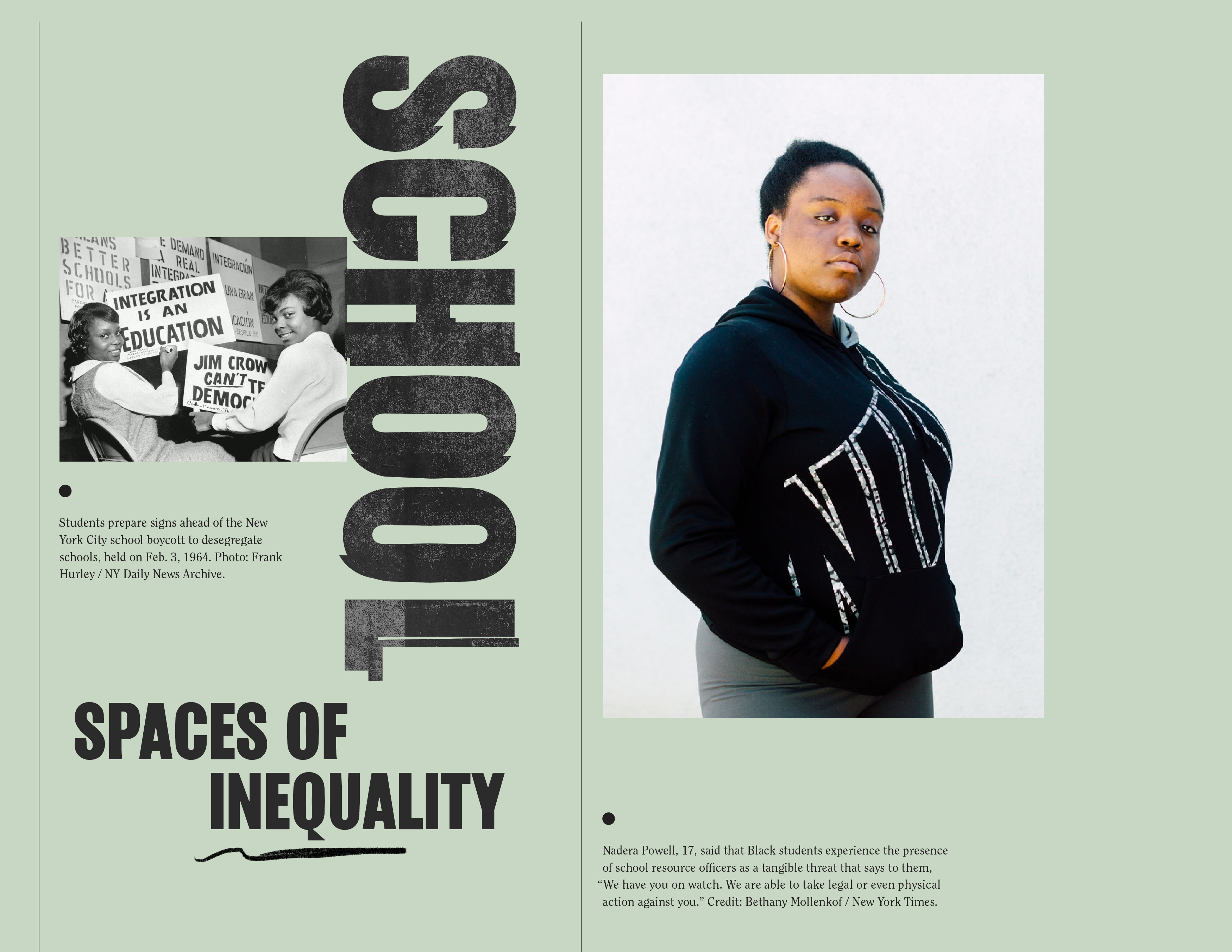

Educational institutions should be

spaces of learning and nurturing for children. For Black kids, however, school is often the first site of stereotyping, mistreatment, and violence. The presence of school police or “resource” officers, security cameras, and metal detectors in many schools have the effect of intimidating Black students, who are subjected to higher proportions of arrests and suspensions. Many minor situations escalate into excessive force and arrests by school police officers. Some describe the ongoing process of pushing students of color from schools into the criminal justice system as the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

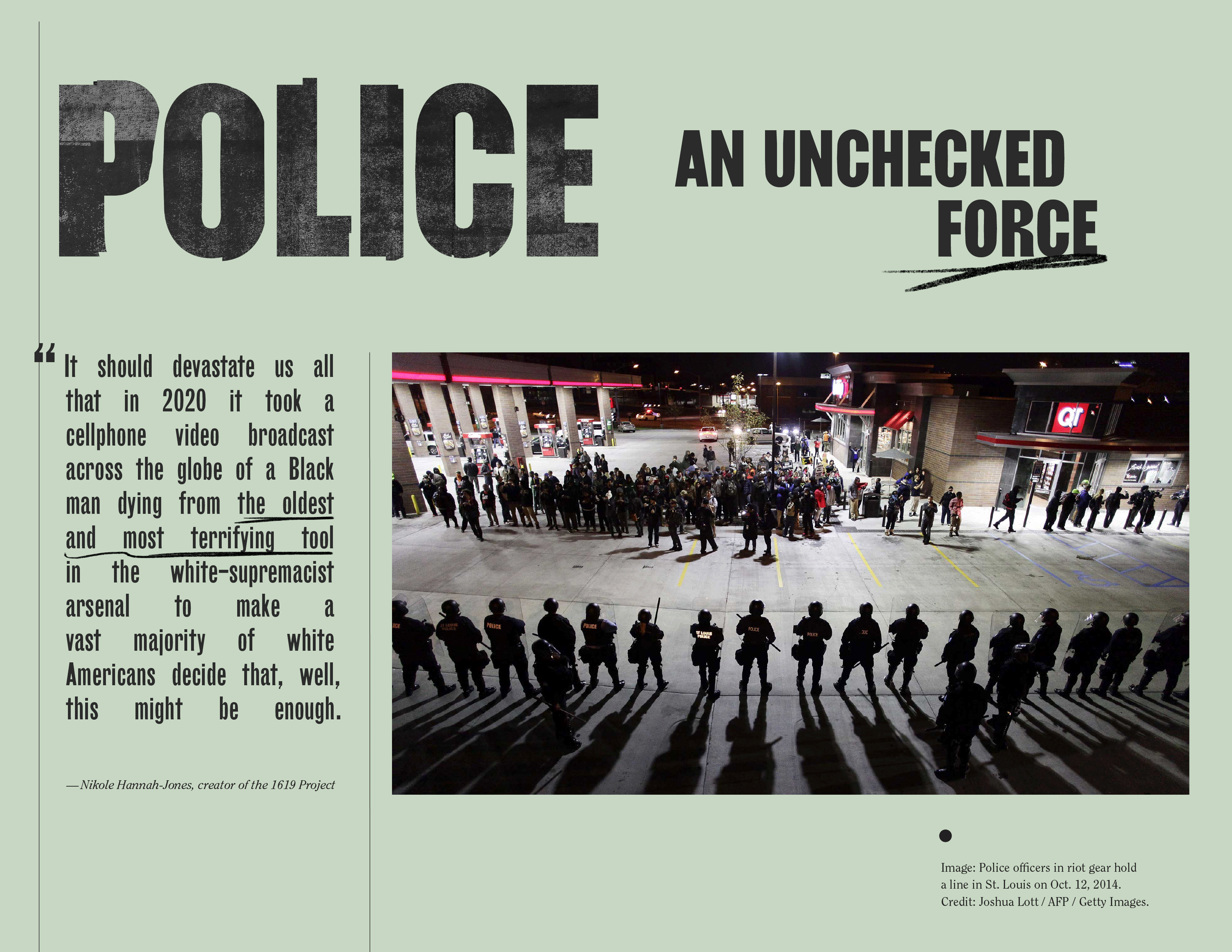

Overreaching police departments

are common today, but this wasn’t always the case. Originally, they were meant to respond to crime, but as time went on, police became a force for surveilling the public under the guise of “crime prevention.” The people labeled as “potential criminals” were often Black or from other marginalized groups that the elite wanted to suppress. Combine this with the power to arrest people arbitrarily, and policing becomes a perfect system of control. Strikingly, in a survey of 75 U.S. cities, 60% of police officers did not live in the communities they oversee. In effect, police forces have become an armed occupation for many Black communities.

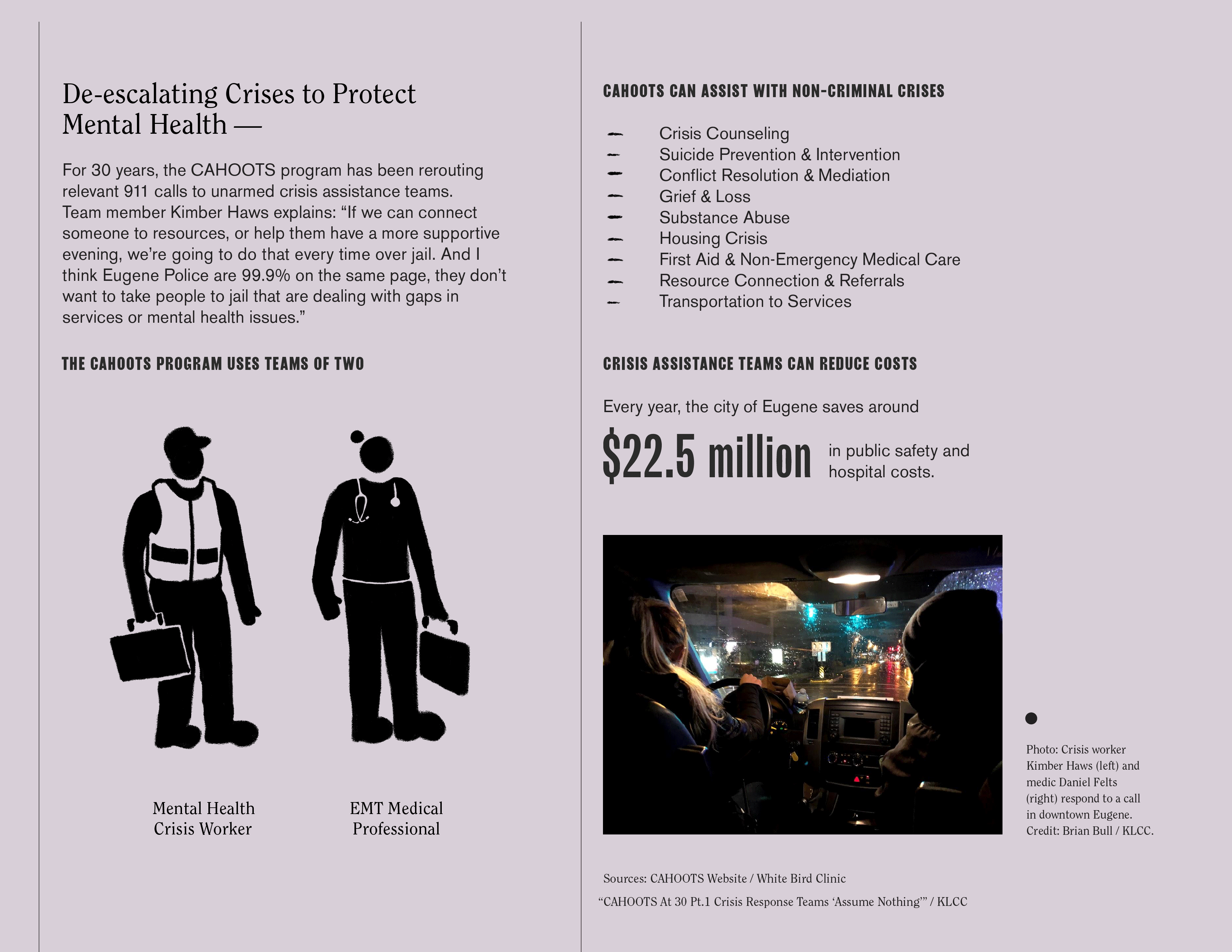

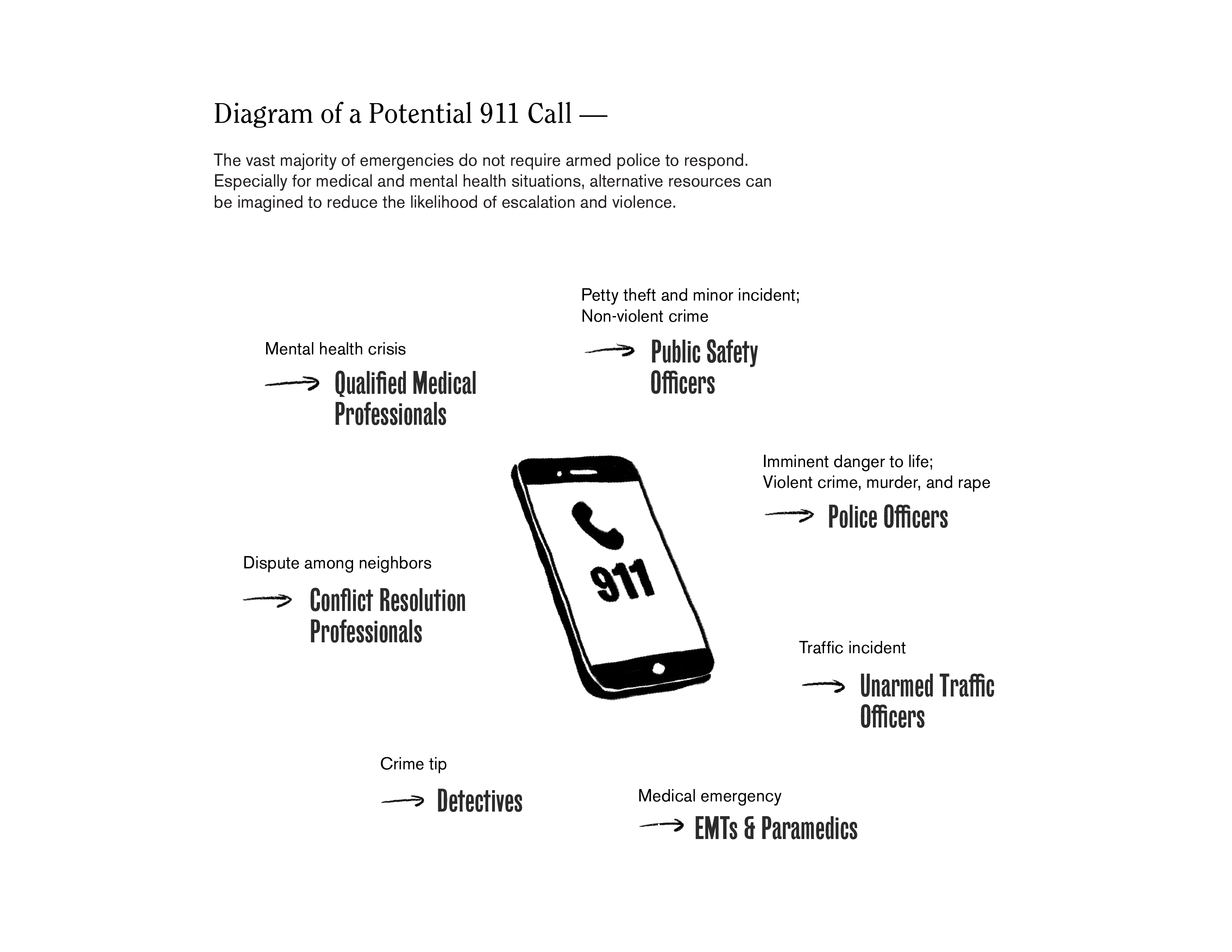

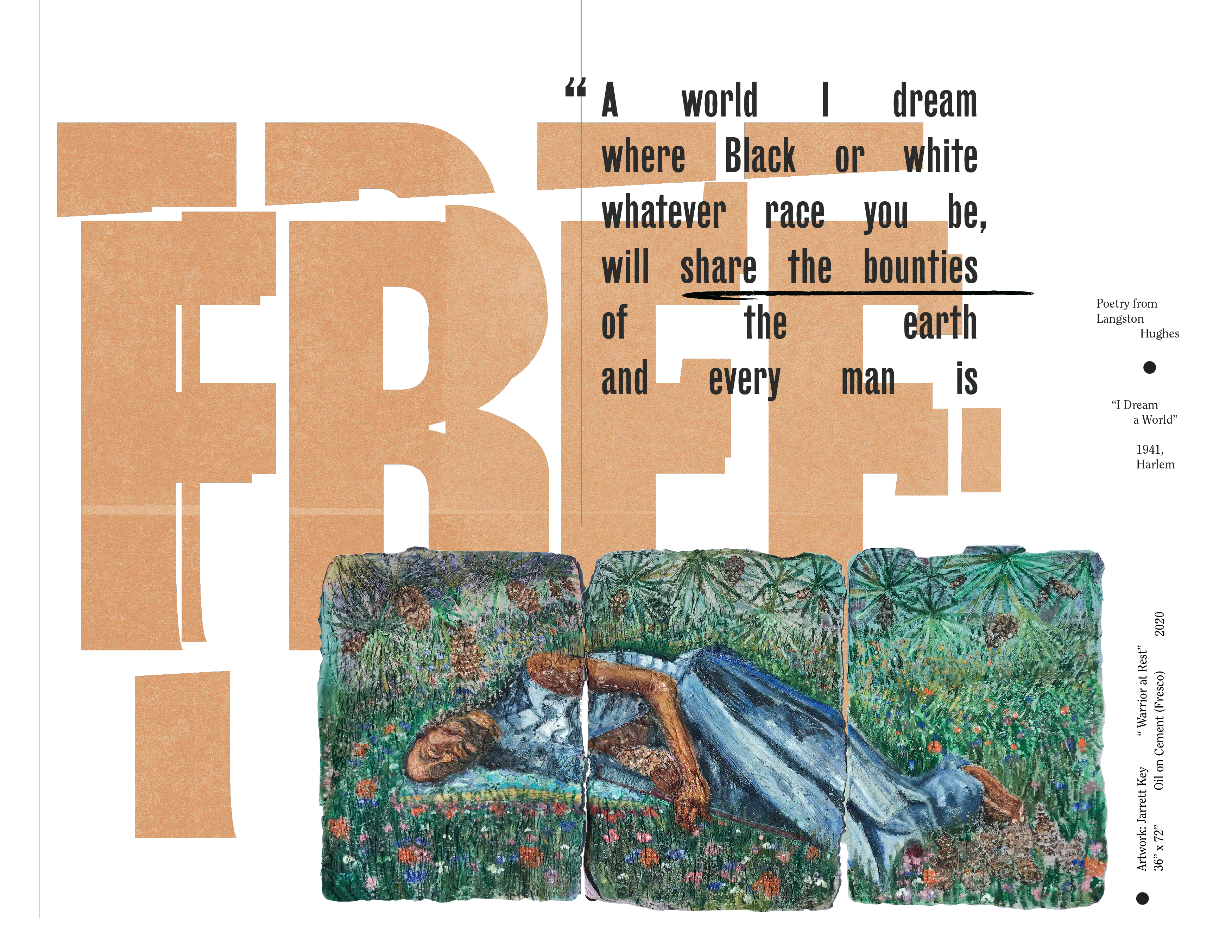

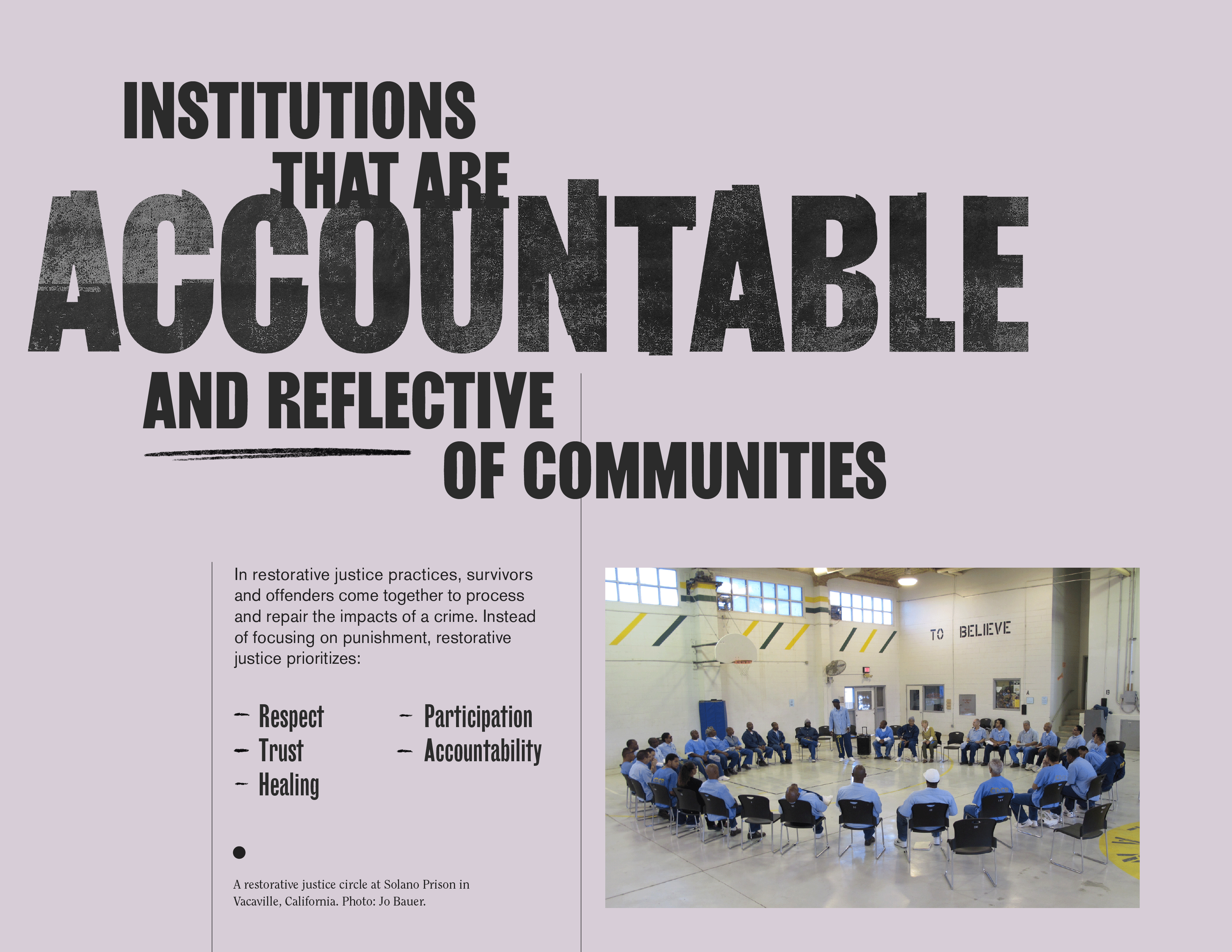

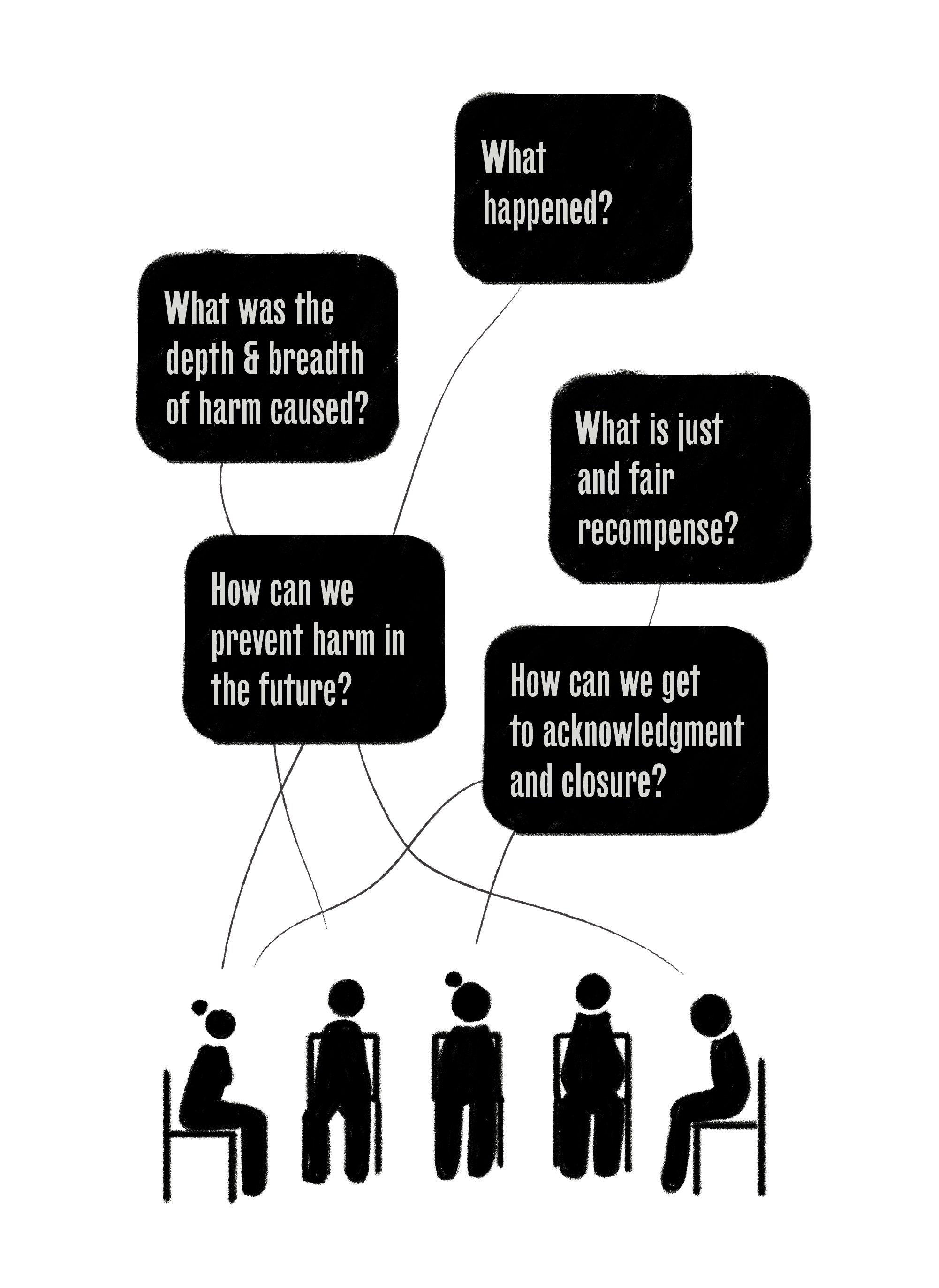

In the midst of dissecting

all of the particularities of what is broken in our criminal justice system, it can sometimes be difficult to pause and imagine what a safe, healthy, and prosperous society might look like. As people alive in 2020, we must unflinchingly bear witness to injustice, speak out, and work to redress it. Yet, it is important that we also find time and space to step back from the entangled web of systemic oppression and imagine alternative systems to ensure the safety and well-being of Black Americans. The following case studies examine specific methods through which communities have sought to address criminal justice with equity.